Remember that groundbreaking gadget everyone swore would revolutionize everything? It vanished faster than your phone battery during a software update. Tech history is packed with “game-changing” products that face-planted despite serious hype. Massive budgets couldn’t save them. Genuine innovation wasn’t enough. These failures teach us more about building successful products than most success stories. Each spectacular crash offers hard-earned wisdom about brilliant ideas meeting brutal reality.

9. Sony Betamax (1975)

The infamous Betamax vs. VHS format war is a classic example of how market needs can trump technical superiority.Sharper picture, cleaner audio, rock-solid playback. By 1988, it owned a pathetic 7.5% market share. Quality wasn’t the problem. Runtime was the killer flaw.

Betamax tapes held one measly hour of content. JVC’s VHS format delivered two full hours. That’s enough for an entire movie without tape-swapping mid-action sequence. Sony obsessed over pixel perfection while customers wanted to record “Raiders of the Lost Ark” without missing anything. Sometimes the “inferior” product wins because it solves the right problem. Technical superiority means nothing when you ignore what people actually need.

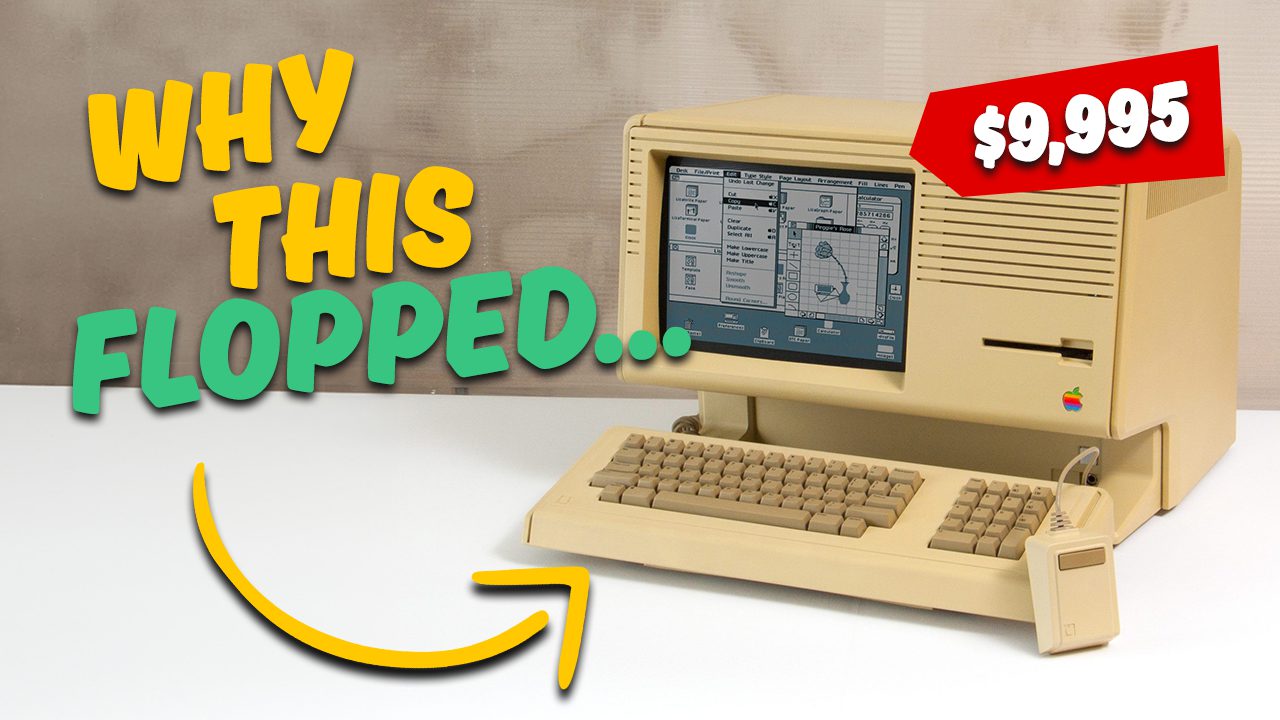

8. Apple Lisa (1983)

Apple’s Lisa pioneered the mouse and graphical interface we use today. It cost $9,995. That’s roughly $31,000 in today’s money. Luxury car pricing for a computer when most systems sold for under $3,000.

Apple moved just 10,000 units in two years. Innovation wasn’t enough. Apple eventually buried unsold Lisa computers in a Utah landfill for a tax write-off. Brilliant technology died because it priced itself out of reach. Lisa walked so Macintosh could run and actually sell.

7. New Coke (1985)

Coca-Cola spent millions perfecting a sweeter formula to beat Pepsi in taste tests. Market research confirmed people preferred the new recipe. What could possibly go wrong? Everything. The New Coke backlash is now a legendary case study in how emotional attachment can override market research.

Seventy-nine days later, the New Coke experiment triggered nationwide outrage. Consumers didn’t want “improved” Coke. They wanted their Coke. Protesters actually held rallies demanding the original formula back. Don Keough, Coca-Cola’s president, later admitted: “All the time and money and skill poured into consumer research on the new Coca-Cola could not measure or reveal the deep and abiding emotional attachment to original Coca-Cola felt by so many people.” Products aren’t just functional items. They’re emotional anchors people refuse to abandon.

6. Nintendo Power Glove (1989)

The Power Glove promised futuristic, gesture-based gaming but delivered clunky, unresponsive controls and worked with only two games. Even generous estimates put sales well under a million units. Despite its commercial failure, the Nintendo Power Glove legacy has left a lasting mark on gaming culture.

Clunky, unresponsive, and compatible with exactly two games, Nintendo’s Power Glove became gaming’s biggest punchline. Sales figures are disputed, but even generous estimates put it well under a million units. The controller required precise hand positioning that made playing games feel like performing surgery. Terrible for a Nintendo accessory. Cool concepts need functional execution. Power Glove was VR gaming 30 years too early with technology 30 years too primitive.

5. RCA SelectaVision VideoDisc (1981)

RCA spent 17 years and $600 million developing an analog video system using vinyl-like discs read by a stylus. Seventeen years. By launch, VHS was dominating home video and LaserDisc offered superior quality for enthusiasts.

SelectaVision was obsolete before hitting shelves. RCA discontinued it after three years, having sold only 550,000 players. The system couldn’t even pause or rewind like VHS could. Lengthy development cycles kill products in fast-moving markets. While RCA perfected yesterday’s technology, tomorrow arrived without them.

4. Microsoft Zune (2006)

Microsoft’s Zune entered the MP3 player market five years after the iPod’s debut. Despite solid hardware and wireless sharing features, Zune never captured more than 10% market share. The rise and fall of Zune is a cautionary tale of late market entry and missed opportunities

Microsoft supported Zune until 2011 but couldn’t overcome Apple’s ecosystem dominance and cultural momentum. The “Zune” name itself became synonymous with second place in tech circles. Late market entry demands either massive innovation or killer pricing. Zune delivered neither. Just decent hardware in a market that had already picked its winner.

3. Google Glass (2013)

Google Glass promised mainstream augmented reality with a head-mounted display showing information in your field of vision. Instead, it sparked privacy fears and social awkwardness. Early adopters earned the nickname “Glassholes.”

At $1,500 with limited apps, unclear use cases, and major privacy concerns, Glass retreated to enterprise markets where looking weird matters less than hands-free data access. Restaurants and bars actually started banning Glass wearers from their establishments. Revolutionary products need to solve social adoption problems, not just technical ones. Nobody wants to be the cyborg at dinner.

2. LaserDisc (1978)

LaserDisc delivered superior video quality and introduced the first consumer optical disc format. Should have been a slam dunk. Instead, it remained niche entertainment for videophiles who didn’t mind paying premium prices.

Discs cost more than VHS tapes, couldn’t record content, and required players costing over $1,000. Movie studios loved LaserDisc’s superior quality but consumers voted with their wallets. VHS offered “good enough” quality with recording capability at fraction of the price. Perfect picture quality couldn’t overcome practical limitations and sticker shock.

1. Digital Audio Tape (1987)

DAT offered perfect digital recording in compact cassette format. Exactly what the music industry feared. Record labels lobbied for copy protection legislation, delaying the US launch for years while cheaper alternatives gained ground.

Legal battles ended too late. DAT’s moment had passed. Professional recording studios embraced DAT while consumers moved on to cheaper CD players and eventually MP3s. It became expensive professional equipment instead of the consumer revolution it could have been. Even technically superior products die when regulatory and industry resistance strangles market access.

0 Comments